Scott Manning

Independent Scholar1

When writer and director Tony Giglio crafted a female lead for his sci-fi horror film Doom: Annihilation (2019; inspired by the popular Doom video games by id Software), he was influenced by a combination of Terminator’s Sarah Conor, Alien’s Ellen Ripley, and Joan of Arc, the latter of which he attributed to his twelve years of Catholic school.2 Lt. Joan Dark, played by Amy Manson, is part of a team of UAC Marine Special Ops that encounter fireball-throwing demons from Hell.3 On the surface, the comparisons end at the character’s name; a deeper reading of Doom: Annihilation, however, reveals that Joan Dark channels much of her namesake’s romanticized plot while also moving outside the director’s original aesthetic vision to provide parallels for often neglected aspects in Joan of Arc’s military career, particularly after her failure at Paris. Understanding the film’s inspiration and links, intentional or otherwise, to Joan of Arc’s story provides a creative tool for exploring an oversaturated yet complex medieval figure.

Figure 1: Still from Doom: Annihilation (Universal Pictures Home Entertainment, 2019)

Giglio consciously decided to create a female protagonist, the first of a Doom movie or video game, saying he ultimately came to Joan of Arc because “[i]f there’s demons, in my logic, then there was [sic] angels. So if there was Hell, there was Heaven. And who better to fight a demon than an angel?”4 He then “started thinking of a religious warrior that would be able to fight demons. A Joan of Arc popped up in my head.”5 However, Joan Dark is no angel or religious warrior, and many of her characteristics seem designed to counter her namesake. For example, although Dark wears a cross necklace her mother gave her, she admits she lost her faith long ago when her mother died fighting cancer. Dark also had a previous romantic relationship with a scientist who is part of the crew, going against the moniker La Pucelle (“the Maid”) Joan of Arc gave herself.6 Dark curses throughout the film, even encouraging others to curse, countering Joan of Arc’s well- chronicled anti-cursing admonishments given to fellow comrades and strangers alike.7

Doom: Annihilation is a sci-fi horror film of the shoot-em-up variety in which virtually everyone but the protagonist dies. Joan Dark and a group of Marines awake from a four- month crypto-sleep upon arriving at Phobos, a moon of Mars, where they are tasked with providing security to a research facility hosting an ancient portal paired with another in Nevada (Earth). Before the Marines arrive, scientists attempt to teleport a human and things go awry. The Marines are unable to contact anyone at the facility and they must force their way in, learning that the main power is down, and reserve power is nearly drained. The Marines must then find a way to restart the facility’s nuclear reactor to prevent a meltdown. In the process, they encounter a few survivors, demons, and zombified humans.

Channeling Joan of Arc in Film

Cinematic medievalism studies have been indulging in Joan of Arc’s avatars for decades with clearly defined guidelines.8 Robin Blaetz defines the romance plot that is the conventional form of Joan of Arc’s story; Blaetz highlights specific phases or markers that have “developed over the centuries through the chronicles, literature, visual art, and biographies in which the story has been transmitted.”9 There is first the prophetic birth or arrival, followed by an innocent youth, which is interrupted by the quest, featuring saints, voices, or some sort of calling. Then there is the downfall or capture, followed by the inquisition, which seemingly unravels all the positive results of the quest. Finally, there is the execution, typically by fire, which brings some sort of fulfillment or alignment to the natural order.10 In the exploration of Joan’s cinematic avatars, many of these phases are metaphoric, and not all avatars will experience each phase in this exact order. The romance plot is, however, a framework to analyze films channeling Joan of Arc.11

Doom: Annihilation matches “Channeling Joan,” one of three general categories Kevin J. Harty establishes for films “in which characters channel Joan as an avatar to advance a number of agendas,”12 whether titular (the character simply shares the name), or deeper (the character is inspired by or even parallels some of Joan’s story).13 One example of channeling Joan comes from Anat Zanger, who identified Ellen Ripley in Alien³ (1992) as a cinematic Joan of Arc in disguise.14 Zanger’s analysis does not focus so much on the phases of the romance plot, but instead on common aspects of Joan’s story, including “voices, the mission, the obstacles on the way to achievement, a change of dress, shaving the head (optional), success, interrogation, betrayal, death by fire and recognition (limited) after death.”15 Some of Zanger’s points are literal, but others, such as the voices, are more creative, focusing on Ripley’s previous encounters with aliens that “provide her with special knowledge,”16 or her interrogation by a male commander who, “like Joan’s interrogators when her answers do not suit their expectations, decides to imprison her (in the installation’s infirmary).”17 Although Ripley skips the first two phases of the romance plot—prophecy and innocent youth—she clearly experiences the remaining phases defined by Blaetz in voices/quest, capture, inquisition, and execution.

Joan of Arc’s cinematic avatars, including Ripley, often do not develop her martial prowess. Yet as Jacques Darras instructs, “[l]et us not pretend, and do as if Joan had been no warrior.”18 Historians have argued that understanding Joan’s story means understanding her warrior life: Kelly DeVries asserts that “Joan of Arc was a soldier, plain and simple. If that is understood, Joan’s other characteristics are also explained.”19 Similarly, although Joan of Arc’s name “is probably the most recognized in medieval history,” Larissa Juliet Taylor laments that “few know more than what they have seen in films” and “even fewer know that Joan was a real soldier and military leader, wounded several times in battle before her capture and execution.”20 More recently, Helen Castor points out that “Joan saw herself as a soldier.”21 Joan’s contemporaries felt the same. After the crowning of Charles VII at Reims, Christine de Pizan rejoiced as “enemies flee before her, not one can last in front of her. She does this, with many eyes looking on, and rids France of her enemies, recapturing castles and towns.”22 Thirty years after her execution, Pope Pius II reflected on Joan of Arc as “a woman…put in command of the war” and he noted with amazement that all the nobles “eagerly followed the Maid.”23

The predominant cinematic focus on the romance plot can lopsidedly employ a “Joan the saint” prism, complete with prophecies and voices, while skimming over or entirely skipping Joan’s military campaigns. Giglio’s evocation of Joan in Doom: Annihilation appears purely titular with no deeper meaning or agenda other than to present an “angel” fighting demons. As such, Dark’s promiscuity, cursing, and disdain for religion discourages a reading of the film through a “Joan the saint” prism. However, by viewing the Joan Dark character through a “Joan the soldier” lens, the movie provides parallels to Joan of Arc’s military career, especially the period between Paris and Compéigne. I thus will examine the parallels to Joan of Arc in Doom: Annihilation by following (roughly) the chronology of the film, beginning with unique aspects connected to a post-Paris Joan and her experience with artillery. I will then explore more conventional parallels in the romance plot, such as voices, inquisition and abjuration, fire, and, finally, capture.

Joan of Arc After the Failure at Paris

With few exceptions, most films skip from the coronation of Charles VII at Reims (July 17, 1429) to Joan’s capture at Compiègne (May 30, 1430), foregoing more than ten months of military operations.24 This omission is not limited to cinema, though. In his seminal Joan of Arc: A Military Leader, DeVries rightly complains that “many of the details of Joan’s campaign on the upper Loire cannot be known, for the sources on her life are fewer for this period,” as many fifteenth-century sources, such as Journal du siege d’Orleans, the Chronique de la Pucelle, Perceval de Cagny’s chronicle, and even the Nullification Proceedings, provide little to no detail.25 Even Pius II, who wrote at length about Joan’s exploits up to her wounding at Paris, summed up the period through her capture at Compéigne with “she accomplished nothing memorable.”26 Still, we know that after her failure to capture Paris (September 1429), she was involved with the capture of Saint-Pierre-le-Moûtier (November 1429) and the failure to capture La Charité (24 November-23 December 1429).27 Joan was not the leader of these campaigns, and the military force was much smaller than previous sieges and battles at Orléans, the Loire Campaign, and the march to Reims. Joan’s failure to capture Paris tarnished the perception of her divine backing. She was thus sent with a smaller and ill-equipped army, to fight against a target she did not choose, and without the leadership position she enjoyed at Paris.

Doom: Annihilation begins in this neglected military phase of Joan’s life, skipping over the typical romance plots to center the story in the nadir of Lt. Joan Dark’s career. Dark awakens from crypto-sleep, bearing scars from previous battles. Similarly, Joan of Arc was wounded on several occasions including an arrow to the chest or shoulder at Orléans, a rock to the head at Jargeau, and an arrow to the leg at Paris.28 Lt. Dark is not in command of her team: she has been demoted for disobeying orders, and her team have lost respect for her; they do not even want to eat in the same room as her, and one Marine openly blames her for what he calls a “shit assignment” in the form of a “three- year tour to the fucking Doomed Moon.”29 The Marines lament that their destination, Phobos, is not only unstable, but also “the very worst draw a UAC Marine can get” and equate it to “babysitting.”30

These exchanges resonate with a little discussed aspect of Joan of Arc’s military career. After Paris, undersupplied and understaffed, Joan was sent to battle a lesser opponent in the form of a mercenary, Perrinet Gressart.31 Although her forces were successful in capturing Saint-Pierre-le-Moûtier, they failed to capture La Charité after nearly a month.32 Surviving letters from Joan and Charles d’Albret, the commander of the campaigns, reveal they begged cities for basic supplies and gunpowder ingredients.33 In their final flight from La Charité they abandoned much of their artillery, likely due to exhaustion and the rough winter weather that traditionally wreaks havoc on military logistics.34 When Joan was interrogated about her failures at La Charité in her condemnation trial, the assessors asked if God ordered her to capture the town and she responded, “who told you I was commanded so by God?”35 She clarified her wish to fight elsewhere, but the directive was to capture La Charité.36 Even Joan, then, was lackluster about her target.

Is it not possible her fellow troops exuded a similar lack of enthusiasm for what a (fictional) UAC Marine might describe as a “shit assignment,”37 especially after retreating and abandoning supplies and weapons at La Charité? Moreover, Pius II tells us that, after Paris, Joan of Arc was regarded “by the French with less reverence.”38 Through her body language—sighs, reserved responses, and breaking eye contact—Joan Dark comes across as resigned to the demotion and assignment, which may have reflected how Joan of Arc felt during the lengthy siege of La Charité. Like Dark, Joan did not want the assignment, but both women did their duty nonetheless, as good soldiers.

Joan Dark and Artillery

Throughout Doom: Annihilation, Joan Dark is adept with weapons, employing rifles, handguns, grenades, and even a chainsaw to kill monsters. Like her namesake, Dark quickly learns and employs the latest technology of her era. A weapon Dark had “only read about” is the BFG9000,39 a comically massive railgun stockpiled in the Phobos research facility (Figure 2). This weapon is a reoccurring trope in the Doom franchise, and Dark clarifies that Marines affectionately refer to it as the “Big Fucking Gun.”40 Dark’s lack of practical experience with the weapon does not hold her back: she declares she is “ready to pop” as she incinerates monsters.41

Figure 2: Still from Doom: Annihilation (Universal Pictures Home Entertainment, 2019)

Dark’s quick affinity with the BFG9000 parallels Joan of Arc’s adeptness with the fast- evolving technology of gunpowder artillery, prowess attested by her comrades.42 Historians vary on how Joan became so quickly skilled with gunpowder: one theory indicates that she was more apt to listen and learn from common cannoneers than commanders descended from the nobility.43 Another theory is her youth: John Aberth suggests that “just like teenagers today, she had an aptitude for the latest technology, in this case, gunpowder.”44 Remarkably, few films portraying Joan of Arc even depict gunpowder artillery in action, and only Cecil B. DeMille’s silent film Joan the Woman (1916) shows her directing cannoneers’ aim.45 Doom: Annihilation provides a refreshing hands-on demonstration of a Joan quickly grasping unfamiliar weaponry, an aspect sorely missing from traditional Joan of Arc films.

Joan Dark’s Voices

Despite its innovations, Doom: Annihilation also participates in the traditional romance narrative. Joan Dark encounters two voices: one that fails her, and another that encourages her to complete her quest for survival. “Daisy” is the computerized voice of the UAC Marines ship and is, at first, benign, fulfilling many sci-fi tropes by executing verbal commands and computing difficult equations. However, early in the film, the ship’s system is infected by a demonic presence and Daisy misbehaves. She is sporadically muffled and unresponsive, eventually becoming deceitful when she misdirects the Marines trekking through the facility’s unfamiliar maze. At a critical juncture, Daisy disables the Marines’ personal communications, causing havoc and confusion. Dark finally realizes Daisy is wholly unreliable when the computer tells her that the pilot is on the bridge of the ship while Dark can clearly see the bridge is empty.46

The unreliability of Joan of Arc’s voices, or her interpretation of them, has been explored in other films; the most extreme is arguably The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc (1999), where her voices are reduced “to phantoms of her own fevered psyche.”47 The difference, of course, is that Joan is merely challenged by her accusers and her own conscience about the validity of her voices. Dark, meanwhile, has visual evidence that the once reliable voice (computer) has turned trickster.

Daisy’s voice is not the only one Joan Dark hears, however. Right before Joan wakes from crypto-sleep and again at the action climax, she encounters a vision of her dying mother. Although portrayed as a dream, Joan’s mother is more akin to a vision: the film retroactively establishes that a person does not dream in crypto-sleep. Despite this impossibility, Dark’s mother instructs her to “[h]ave faith that in your darkest moment, you won’t be alone. I’ll be there, watching over you.”48 The camera cuts to Joan’s eyes opening as she hears her mother again: “Believe in yourself, Joan” (Figure 3).49

Figure 3: Still from Doom: Annihilation (Universal Pictures Home Entertainment, 2019)

Dark’s lack of faith is well established to the point that a Marine chaplain will use his dying moment to reinforce the narrative’s emphasis that the mother is a vision, not a dream, telling Dark that “[s]he’s still with you…I can see her spirit all around…it’s beautiful.”50 Dark hardly has time to process this dying declaration before rushing to the next crisis. The testimony pays off in the film’s climax when Dark finds herself in Hell, face down on the ground with a swarm of demons rushing toward her. She sees the reflection of her cross necklace in a pool of water, evoking the crypto-sleep vision along with her mother’s final words. Fitting Giglio’s aesthetic vision of employing an “angel” to fight demons, this maternal voice gives Dark courage to push forward against insurmountable odds,51 mirroring Joan of Arc’s own understanding of her voices as saints.

The Inquisition and Abjuration of Joan Dark

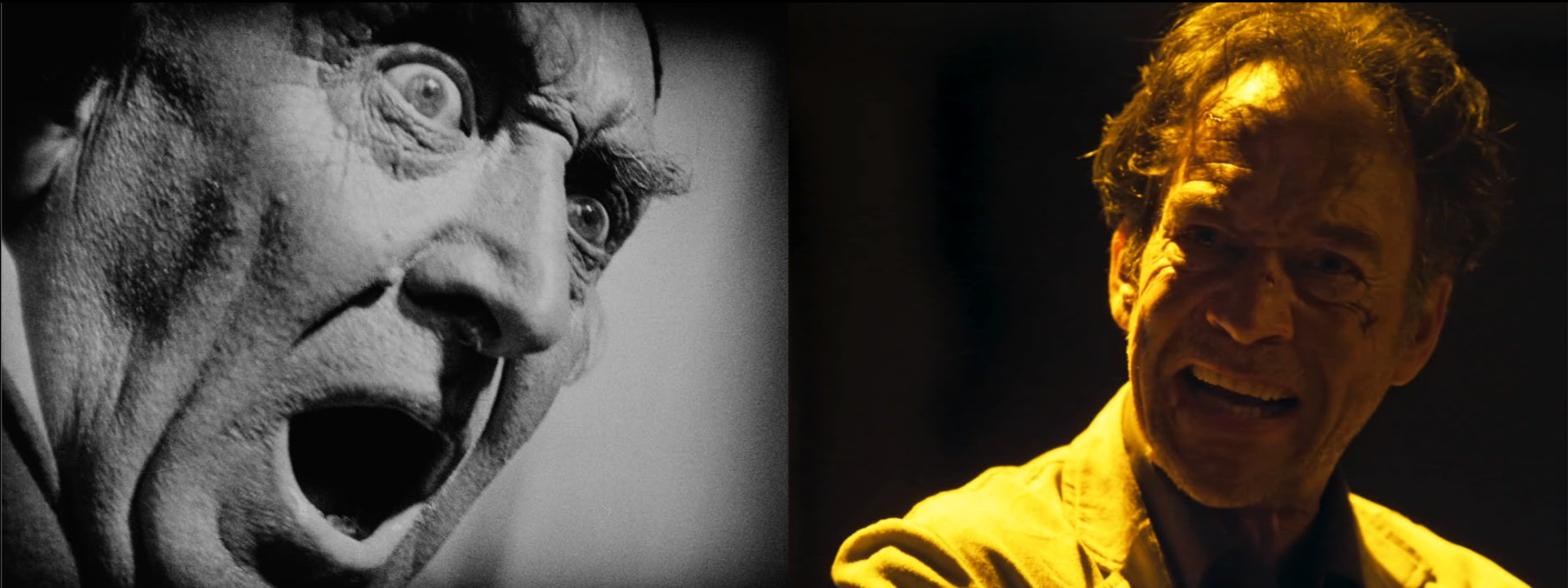

Another phase of the romance plot is inquisition. Joan Dark assumes command, intending only to restore the facility’s nuclear reactor while waiting for backup. Her decision is challenged by Dr. Malcolm Betruger (Dominic Mafham), a scientist who survived the initial massacre yet wishes to replicate many of the fatal steps instead of securing the base. Betruger is antagonistic toward Dark, operating as a modernized Bishop Pierre Cauchon, Joan of Arc’s primary judge at her condemnation trial. The doctor reveals that he has read the official reports of a “review board” of Dark’s last mission, where she disobeyed a direct order and freed a dangerous terrorist. The scene evokes the dramatic staging of Joan’s trial in Carl Dreyer’s silent film La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928).52 Dark endures Betruger’s accusations and expresses her torment predominately through her body language: side looks to her fellow Marines, breaking eye contact, and trying (but failing) to act as if the moment is not phasing her (Figure 4).53 Though Dark and her Marines are positioned around the room, the camera isolates Dark as she relives the accusations. Betruger further taunts Dark with a sadistic smile, mirroring Joan’s accusers in La Passion.

Figure 4: Stills from Doom: Annihilation (Universal Pictures Home Entertainment, 2019), left, and La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (Société Générale des Films, 1928), right.

Betruger’s interrogation is rhetorical, but designed to provoke Dark into second guessing her actions: “Was it your ego, Lieutenant? Or did you just know better? Or did you just make a mistake? We all make mistakes. I certainly do.”54 He next turns to quoting the testimony of Dark’s fellow Marines to undermine their confidence in her leadership, reminding all in the room that they had stated “Lt. Dark was incompetent, should be arrested, and dishonorably discharged,” and other Marines had “asked to be reassigned, citing that you could never trust Lt. Dark again.”55 The interrogation is not calm, because Betruger is not actually questioning Dark: he yells “Treason! Which carries the death penalty!”56 to distract the Marines, not to elicit a confession from Dark. He is successful: Betruger locks the team in the reactor room alongside monsters. Although Doom: Annihilation lacks the intensity of claustrophobic closeups with vignetting that visually characterize La Passion, when Betruger faces Dark during the intense confrontation a shadow covers his face to emphasize his turn to villainy (Figure 5).57 Dark is framed alone, staring in the distance, as she guards one side of the room and endures the verbal assault.

Figure 5: Stills from La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (Société Générale des Films, 1928), left, and Doom: Annihilation (Universal Pictures Home Entertainment, 2019), right.

Betruger’s trap kills all the Marines but Lt. Dark, and, after she escapes the trap, Dark tells a surviving scientist that the accusations against her were true. She thought she “knew best” and that she “could be a hero,” which led to a terrorist escaping.58 She shows remorse, admitting it was her fault that her unit was assigned to Phobos and “now my whole team’s dead.”59 She concludes, “Guess it’s a good thing I don’t believe in Hell, right?”60 This moment of self-doubt and reiteration of Dark’s lack of faith parallels the abjuration of Joan of Arc where she signed a document admitting that she made up her saintly voices and promised to stop wearing men’s clothing. Joan later recanted, leading to her execution by fire a few days later.61 Dark’s moment of doubt is short lived: the surviving scientist claims that “the best way to honor your team’s memory right now” is to kill Betruger, setting up the film’s final confrontation.62

Joan Dark, Fire, and Capture

Fire reoccurs throughout Doom: Annihilation in the threats of nuclear meltdown and the monsters that a chaplain describes as “demons made of fire.”63 Joan Dark and her fellow Marines dodge many of these fireballs, but several of them succumb to direct hits. Dark’s BFG9000 dispenses its own fire in the form of a green blast. The most appropriate fire parallel is Dark’s attempts to escape Hell (within the Doom franchise, the monsters are understood to originate from Hell), which the film establishes as a dark canyon filled with fireball-throwing demon-monsters. Dark enters Hell when the inquisitor Betruger overpowers Dark with unnatural strength and throws her through the portal that the base is designed to guard. However, Dark does not end up in Nevada, nor is she torn apart by the portal; instead she finds herself alone in a dark canyon surrounded by monsters. Strengthened by the vision of her mother, Lt. Dark employs her BFG9000 until she runs out of ammunition and finds a second portal, visualized as a circle of fire. Dark leaps through the portal to escape, throwing grenades at the pursuing demons (Figure 6). Dark’s choice to jump into the fire of her own volition mirrors another cinematic avatar, Ellen Ripley (Alien³), and contrasts Joan of Arc’s own choice.64 Although much is unknown about the portals, Dark’s choice to go into the fire is an attempt at salvation instead of certain death.

Figure 6: Still from Doom: Annihilation (Universal Pictures Home Entertainment, 2019)

Salvation is not certain. The fiery portal leads Joan Dark to the research facility in Nevada, where she encounters scientists ignorant of the fall of the Phobos base. Dark realizes the portal is still open when the scientists ask her if Dr. Betruger is close behind, and she demands that they seal the portal. Eager to protect their research, the scientists argue with Lt. Dark, before apprehending and drugging her (Figure 7). This scene acts as another brief interrogation, but ultimately serves as a parallel to Joan of Arc’s capture. Dark loses consciousness as something comes through the portal and the screen fades amid the sounds of screaming monsters. All the work Joan Dark did while in Hell, from firing the BFG9000 until she runs out of ammunition to hurtling grenades, is seemingly for naught. The howls of the monsters demonstrate that Dark’s warnings were correct and her interrogators have damned themselves.

Figure 7: Still from Doom: Annihilation (Universal Pictures Home Entertainment, 2019)

Channeling Joan of Arc in Doom: Annihilation

Doom: Annihilation selectively reorders phases from the Joan of Arc romance plot. The film avoids two key phases, prophecy and innocent youth, and focuses on the often- neglected military phase. Lt. Joan Dark, who is no saint, is a career soldier. The viewer watches her do her duty while living with her scars and failures. Dark’s shameful posting to Phobos highlights a period in Joan of Arc’s military career that featured similar challenges with a lackluster assignment and discouraged comrades who doubted her. Blaetz’s analysis of another Joan of Arc cinematic avatar, found in Joan of Paris (1942), notes how by embracing the romance plot of her story, the film is able to “increase the sense of inevitability.”65 In addition, the film “allows [the] patriarchy to have its heroines and burn them, too.”66 Similarly, viewers of Doom: Annihilation witness Joan Dark experience otherworldly voices, interrogation, capture, and fire. There is even a quest for survival and brief abjuration, all leading to a climax demonstrating that, despite characteristics constructing Joan Dark as a mirror avatar of Joan of Arc, both Joans share the same fate for many of the same reasons.

Medievalists sometimes look to cinematic medievalism to help undergraduates enter the field, and the plethora of Joan of Arc films serve as co-texts for historical analysis and lively classroom discussions.67 John Aberth has argued that after La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), “it is almost pointless to talk of any other Joan of Arc Film,”68 and Edward Benson discouragingly demonstrates that no single film is “useful in helping their students appreciate the challenge posed by the Maid’s short public life,” concluding that no one can adequately produce a “film to meet that challenge.”69 Benson reviews four different films and ranks them from “deeply flawed” to “useful,” yet still failing “to capture some of the contradictions enacted in her story.”70 Despite these problems, Benson finds merit in screening selections of Joan of Arc films with students, while the teacher supplements with discussion and context.71 Daniel Hobbins suggests, more optimistically, that Joan of Arc films “are a wonderful way to introduce students to one of the most fascinating figures in history.”72 These approaches involve selecting extracts from traditional Joan of Arc films and Benson believes that coupled with engaging “our students in discussion of why it has proved so difficult to film Joan’s short and violent public life” is “the best we can do.”73 I suggest augmenting the methods of Benson and Hobbins to include extracts from films channeling Joan of Arc, several of which have been identified by Kevin J. Harty.74 By examining Joan of Arc’s avatar in unlikely films such as Doom: Annihilation, medievalists are equipped with more cinematic introductions to her story, highlighting a period often passed over silently in cinema and historical records alike.

- I want to thank the readers and editors for their contribution to this paper. They engaged and challenged the thesis, leading to a much tighter and stronger version.

- Alex Kane, “Writer-Director Tony Giglio on Making Doom: Annihilation,” Forbes, October 1, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/alexkane/2019/10/01/writer-director-tony-giglio-on-making-doom-annihilation/ (accessed July 5, 2020).

- Doom: Annihilation, directed by Tony Giglio (Universal Pictures Home Entertainment, 2019). Although the movie never explicitly states that these monsters come from Hell, those familiar with the video game series know this as the source of these monsters.

- Quoted in Kane, “Writer-Director Tony Giglio on Making Doom: Annihilation.”

- Quoted in Allan McKay, “Episode 220—DOOM—Film Director Tony Giglio,” The Allan McKay Podcast, November 12, 2019, https://www.allanmckay.com/220/ (accessed July 6, 2020).

- As Helen Castor points out, by “referring to herself as ‘Jeanne la Pucelle,’ ‘Joan the Maid,’” she had adopted “a title redolent with meaning, suggesting not only her youth and purity but her status of God’s chosen servant and closeness to the Virgin, to whom she claimed special devotion.” Helen Caster, Joan of Arc: A History (New York: HarperCollins, 2015), 3.

- See statements made by Seguin Seguin, Gobert Thibault, Réginalde, the Duke of Alençon, and Louis de Coutes in Pierre Duparc, ed. Procès en nullité de la condamnation de Jeanne d’Arc, vol. 1 (Paris: Klincksieck, 1977), 473, 370.

- For numerous examples in English, see Scott Manning, “Joan of Arc on Screen: An Annotated Bibliography,” Historian on the Warpath, July 28, 2018, https://scottmanning.com/content/joan-of-arc-on-screen-an-annotated-bibliography/ (accessed July 5, 2020).

- Robin Blaetz, Visions of the Maid: Joan of Arc in American Film and Culture (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2001), 3.

- Blaetz, Visions of the Maid, 3-7.

- For example, see Robin Blaetz, “Retelling the Joan of Arc Story: Women, War, and Hollywood’s Joan of Paris,” Literature/Film Quarterly 22, no. 4 (1994): 212-221.

- Kevin J. Harty, “The Lady Is for Burning: The Cinematic Joan of Arc and Her Screen Avatars,” In Medieval Women on Film: Essays on Gender, Cinema, and History, ed. Kevin J. Harty (Jefferson: McFarland, 2020), 182.

- Harty, “The Lady Is for Burning,” 192-3.

- See Anat Zanger, Film Remakes as Ritual and Disguise: From Carmen to Ripley (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2006); Alien3, directed by David Fincher (20th Century Fox, 1992).

- Zanger, Film Remakes as Ritual and Disguise, 111.

- Zanger, Film Remakes as Ritual and Disguise, 110. Ripley’s special knowledge comes from the film Aliens (1986, directed by David Cameron). Another, more literal form of voices that Zanger omitted would be Bishop, a damaged android that Ripley barely gets operational to provide her with important plot elements heard only by her. Scott Manning, “Alien3’s Ripley as Joan of Arc,” Historian on the Warpath, July 19, 2018, https://scottmanning.com/content/alien-3s-ripley-as-joan-of-arc/ (accessed July 6, 2020).

- Zanger, Film Remakes as Ritual and Disguise, 110.

- Jacques Darras, “A Myth on Trial,” in Joan of Arc, A Saint for All Reasons: Studies in Myth and Politics, ed. Dominque Goy-Blanquet (New York: Routledge, 2016), 121.

- Kelly DeVries, Joan of Arc: A Military Leader (Phoenix Mill: Sutton Publishing, 1999), 3.

- Larissa Juliet Taylor, The Virgin Warrior: The Life and Death of Joan of Arc (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), xviii.

- Castor, Joan of Arc, 160.

- Christine de Pizan, “The Tale of Joan of Arc,” in The Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan: New Translations; Criticisms, trans. Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski and Kevin Brownlee (New York: W. W. Norton, 1997), 258.

- Florence A. Gragg, trans., Secret Memoirs of a Renaissance Pope: The Commentaries of Aeneas Sylvius Picolomini, Pius II (London: The Folio Society, 1988), 196.

- There are several notable exceptions including The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc, directed by Luc Besson (Columbia Pictures, 1999); and Jeanne la pucelle, directed by Jacques Rivette (Pierre Grise Productions, 1994). Both films depict Joan’s failed siege of Paris, as well as her wounding. For a recent survey of Joan of Arc films, see Harty, “The Lady Is for Burning,” 182-191.

- DeVries, Joan of Arc: A Military Leader, 159.

- Gragg, Secret Memoirs, 200.

- DeVries, Joan of Arc: A Military Leader, 156-185.

- See Philippe Contamine, “Injures,” in Jeane d’Arc: Histoire et dictionnaire, eds. Philippe Contamine, Olivier Bouzy, and Xavier Hélary (Paris: Robert Laffont, 2012), 769-770.

- Doom: Annihilation.

- Doom: Annihilation

- Although not the target she desired, Perrient Gressart was by no means an easy opponent. For more, see Kelly DeVries, “Routier Perrinet Gressart: Joan of Arc’s Penultimate Enemy,” in Routiers et mercenaires pendant la guerre de Cent ans: Homage á Jonathan Sumption, eds. Guilhem Pépin, Françoise Lainé, and Frédéric Boutoulle (Bordeaux: Ausonius, 2016), 227-37.

- Castor, Joan of Arc, 149.

- Text of letter available in Craig Taylor, trans., Joan of Arc: La Pucelle (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2006), 130-31.

- Castor, Joan of Arc, 149-50.

- Testimony given on March 3, 1431. See Daniel Hobbins, trans., The Trial of Joan of Arc (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005), 84.

- Hobbins, Trial of Joan of Arc, 84.

- Doom Annihilation.

- Gragg, Secret Memoirs, 200.

- Doom: Annihilation.

- The gun was introduced in the earliest releases of Doom in 1993 and versions of it have appeared in every incarnation since. A detailed description of the gun’s power and limitations available in Dan Pinchbeck, DOOM: SCARYDARKFAST (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013), 102-104. Also informative is Federico Alvarez Igarzábal, “Chekhov’s BFG,” in Time and Space in Video Games: A Cognitive-Formalist Approach (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2019), 191-206.

- Doom: Annihilation.

- Doom: Annihilation.

- DeVries, Joan of Arc, 56; Jack Kelly, Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World (New York: Basic Books, 2005), 47.

- John Aberth, A Knight at the Movies: Medieval History on Film (New York: Routledge, 2003), 264. Similar points made in Kelly, Gunpowder, 47.

- IJoan the Woman, directed by Cecil B. DeMille (Paramount, 1916).

- Doom: Annihilation.

- Nickolas Haydock, Movie Medievalism: The Imaginary Middle Ages (Jefferson: McFarland, 2008), 126.

- Doom: Annihilation.

- Doom: Annihilation.

- Doom: Annihilation.

- Doom: Annihilation.

- La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer (Société Générale des Films, 1928).

- Although Amy Mason (left) never reaches the levels of agony expressed by Renée Jeanne Falconetti (right), there are similar moments of self-doubt and resignation conveyed during both actresses’ interrogations.

- Doom Annihilation.

- Doom Annihilation.

- Doom Annihilation.

- On the left, Bishop Pierre Cauchon threatens Joan of Arc with torture if she does not adjudicate. On the right, Dr. Malcolm Betruger antagonizes Lt. Joan Dark, claiming she committed treason and deserved the death penalty.

- Doom: Annihilation.

- Doom: Annihilation.

- Doom: Annihilation.

- Castor, Joan of Arc, 190-193.

- Doom: Annihilation.

- Doom: Annihilation.

- Zanger, Film Remakes as Ritual and Disguise, 111.

- IBlaetz, “Retelling the Joan of Arc Story,” 220. Joan of Paris, directed by Robert Stevenson (RKO, 1942).

- Blaetz, “Retelling the Joan of Arc Story,” 220.

- For example, Edward Benson, “Oh, What a Lovely War! Joan of Arc on Screen,” in The Medieval Hero on Screen: Representations from Beowulf to Buff, eds. Martha W. Driver and Sid Ray (New York: Routledge, 2004), 217-36.

- Aberth, A Knight at the Movies, 290. It is unlikely that Bruno Dumont’s recent musicals would change this bleak assessment. Jeannette: The Childhood of Joan of Arc, directed by Bruno Dumont (Toas Films, 2017); Joan of Arc, directed by Bruno Dumont (3B Productions, 2019).

- Benson, “Oh, What a Lovely War,” 230.

- Benson, “Oh, What a Lovely War,” 217.

- Benson, “Oh What a Lovely War,” 217.

- Daniel Hobbins, “The Cinematic Maid: Teaching Joan of Arc Through Film,” Fiction and Film for French Historians: A Cultural Bulletin 2, no. 3 (2011), https://h-france.net/fffh/maybe-missed/cinematicmaid/ (accessed 30 August 2020).

- Benson, “Oh, What a Lovely War,” 217.

- Harty, “The Lady Is for Burning,” 192-196.