Alexander L. Kaufman

Ball State University

When one thinks of the band Roxy Music, “medievalism,” “the sublime,” and “ecology” are hardly the first words that come to mind. Formed in 1971 London, Roxy Music was itself an intersectional outfit. Their music was a mixture of a rock and roll with art-rock and glam-rock leanings, and the band’s members were overly conscious of the power that nostalgia played in the lives of its listeners and thus wrote often about the past (or pasts) in such themes as love, rock-and-roll, desire, and that which can never be regained. It was also a band that, much like David Bowie, was concerned with the visual dynamics of music; as such, Roxy Music cultivated a style all its own.1

In this article, I investigate an object and an artistic statement that is both connected to the canon of Roxy Music’s first seven studio albums but also very much apart, and consciously so, from their aural and visual past: their final studio album, Avalon, which was originally released in 1982. Avalon is the final island in the band’s archipelago island chain, connected, though distant. The album is one that has received a few passing remarks from scholars as an artifact of Arthurian and medieval culture, though a closer investigation of its medievalism-ist qualities has not been undertaken.2 Avalon is an album of sublime ecological neomedievalism, for it is an artistic statement on the role that nature plays in the construction of a neomedieval text. The album’s songs, textures, and visuals are filtered through the artists’ own ideas of what is medieval and specifically what is Arthurian, which for Roxy Music is the sublime space, landscape, and soundscape of Avalon/Avalon.

Avalon, and by extension the band and their music at this particular juncture in their history, are distinguished as sublime examples of neomedievalism, which Amy Kaufman describes so succinctly: “The neomedieval idea of the Middle Ages is gained not through contact with the Middle Ages, but through a medievalist intermediary: Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings Series, T. H. White’s Once and Future King … Neomedievalism is thus not a dream of the Middle Ages, but a dream of someone else’s medievalism. It is medievalism doubled up upon itself.”3 As Kaufman and others note, neomedievalist texts and objects are often those that reside in the bottom-end of the culture scale, for they are associated with popular, consumerist values. The album Avalon is concerned with ecological themes, and in fact nature and the physical environment are tropes that run through the work as a whole and help to unite it. For Roxy Music, Arthur’s end and voyage to Avalon allows for the band to explore its own movement toward a space that marks a definite end, though with the potential for renewal. Arthur’s/Roxy’s voyage is one that is situated both within foreign, though familiar, locales, and is thus global in its approach toward British Arthurian medievalism. The end result is a singular, intersectional artistic achievement, one which can be of course enjoyed on its own merits, and also for its neomedieval, sublime ecologically-minded constructs that are present within it.

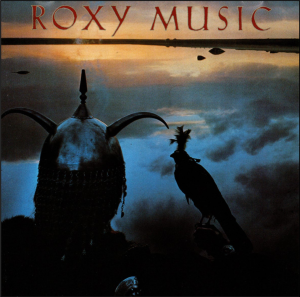

As with most albums, the listener first approaches the work through the visuals of the album sleeve, and it is this striking cover image that introduces the album to audiences. The band’s lead singer and principal songwriter was and remains Bryan Ferry. Significantly, in 1964, Ferry began a degree in fine arts at Newcastle University, and it was there that he studied for one year with the noted British pop artist Richard Hamilton, whose artistic sensibilities, and specifically his 1956 collage What Is It About Today’s Homes That Makes Them So Different, So Appealing, predicted a number of Roxy Music’s records, most notably “In Every Dream Home A Heartache.”4 Hamilton’s pop art manifesto is one that can be transposed onto the world of pop music: “Pop art is: Popular (designed for a mass audience), Transient (short-term solution), expendable (easily forgotten), Low Cost, Mass Produced, Young (aimed at youth), Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky, Glamorous, Big Business.”5 Ferry’s own artistic style at the time, influenced by Hamilton, but also Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol, was one of “cool perfectionism.”6 This artistic style is notable in almost every Roxy Music album sleeve design, most of which involve glamorous models in unusual locales or “on display” in unique poses. The cover art for Avalon, however, dispensed with the sultry and sexualized women of previous albums.7

The cover concept of Avalon brings the viewer and the listener into the medieval and into the ecological sublime: it is a sensorial immersion into the romantic, fictionalized past through sight (and then sound). The cover image itself holds much in common with the visual style of John Boorman’s film Excalibur (1981) with its mists and sharp contrasting styles and lines. One could also locate elements of the cinematic style of Monty Python and the Holy Grail, especially Arthur and Bedevere’s approach to Castle Aaargh.

Figure 1: Neil Kirk’s cover for Avalon (E. G. Records, 1982)

Figure 1.8

For the cover image, Ferry again enlisted his long-time photographer Neil Kirk and designer Anthony Price. Ferry’s instructions to Price were specific: to concoct “a very barbaric, MacBeth-styled outfit.”9 Roxy’s Arthur wears a horned helmet, a velvet gabardine, and Celtic brooch, and a hooded bird of prey is in his right hand. Jonathan Rigby describes how the figure “looks out impassively over a fog-shrouded expanse of lake. The shot was taken in the sunny aftermath of a dawn drizzle, with Price sending fireworks over the lake to whip up a suitably oneiric pall of smoke.”10 In the continuum of Roxy Music album covers, it of course signals the end, the studio album swansong. But this being Roxy Music, there is a slyness about what is actually going on in the image. While we have a sense of linear progression and the final resting place of the group in Avalon, we also have a re-presentation of a traditional Roxy Music album cover. The person in the helmet and cape and holding the falcon was Ferry’s then-girlfriend and subsequent wife (until 2003), Lucy Helmore. For once, the woman on the album cover is fully clothed and baring no skin, a king/queen heading off to Avalon, to have his/her wounds healed. The cover image of the album, and its title, are themselves echoing medieval texts that are themselves echoing films that are themselves examples of neomedievalism: Boorman’s Excalibur, Roman Polanski’s Macbeth, and Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

While the album is building upon centuries of medievalisms, it is also embracing an ecologically minded artistic statement, for the cover artwork and the music exemplify sublime ecology. If we turn, briefly, to Longinus’s remarks on the role that nature plays in the construction of the sublime in art, we can note a continuum of intellectual thought from the classical text to the neomedieval album. For Longinus, Homer’s Illiad and the opening lines of Genesis signal the presence of divine power and its affects on the construction, interpretation, and appreciation of the sublime. In the former, “the whole universe sundered and turned itself upside down” by the Battle of the Gods, but those moments in the texts are “far surpassed by those passages which represent the divine nature as truly uncontaminated, majestic, and pure.”11 But it is in Longinus’s reading of God’s creation of light (Gen. 1.3-9) wherein “the energies of God, rather than the unknowable divine essence”12 form the most evocative image of the power of nature’s energies on the creation of land, air, and water.13 In the eighteenth century, the sublime came to be associated not only with rhetoric but also nature, where “either a landscape … stimulates spiritual awareness or the literary work or painting that captures this elevated quality.”14 Edmund Burke, in his work A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1756), saw the sublime as “more psychological than theological: God was merely one idea that displayed the sublime characteristics of obscurity, power, duration, vastness, infinity, difficulty, and magnificence.”15 When we look at the album cover of Avalon, it is one that is a totalizing experience: secular and sacred, human and non-human, man-made and that created by (or out of) nature. The cinematography of the shot, too, underscores the oblique temporality of the moment as it sublimely captures both dawn and dusk: the figure is either approaching the beginning or the end of his or her life, or both simultaneously. The sublime command/statement “Let there Be Light” certainly reverberates within the album’s image, for it is this light that creates a bridge between the sky, land, and water. Moreover, the light unifies all things as it touches the armor, the water, the air, and thus creates a sweeping image of sublime mystery and wonder. While the armored figure is in the foreground, the focal point of the image (the mise-en-scène of the composition) directs the viewer’s eyes to the rising or setting sun that governs over all; indeed, both “Arthur” and his falcon appear to be gazing in that direction as well. This complex intertwining of the physical world, the temporal plane, and the individual’s interaction with and place within both represent a microcosm of the medieval experience not only for those who lived through it but also for those who re-experience its post-medieval manifestations. The cover image of Avalon is of course a gateway into the album proper. However, it is much more than that, for it serves as an intersectional matrix of environmental beauty, power, serenity, and danger.

The medieval Celtic connection with the elements, so prevalent in Arthurian literature, is here introduced as the physical setting of the album’s cover image. Ferry began work on the album at Crumlin Lodge on the west coast of Ireland with Helmore, and it is from this romantic setting where the cover image was taken. In a special issue of the journal Religion and Literature titled “The Endless Knot”—a title that evokes both Celtic and also Arthurian iconography, especially the poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight—Terry Eagleton sees in Burke’s definition of the sublime something that the cultural critic identifies as the “Irish Sublime,” and it is one that is inherently connected with the natural world.16 Eagleton’s reading of Burke is prescient, particularly when we consider the ecology of Avalon, and the physical, Irish and Celtic elements in the cover image and in the album’s closing song “Tara,” which I will discuss shortly. For Eagleton, the “Irish Sublime” has its origins in the Middle Ages and “the greatest of all Irish theologians,” Johannes Scottus Eriugena,17 an individual whom Alfred Kentigern Siewers argues created “a hidden lineage of alternative views of nature,”18 and whom Eagleton believes saw the natural world

as an underground play of self-delighting difference, an infinity of partial perspectives, an anarchy of unbridled non-identity. . . . It was a theology that stressed the sensuous immanence of God, the littleness and frailty of Jesus, the jouissance of Nature, the ordinariness of the marvelous. . . . For Eriugena, as a kind of Romantic Idealist avant la lettre, God was incarnate in the very structures of human subjectivity, in that anarchos of the human spirit which makes human nature in principle boundless, omniscient and infinite, and so a creative sharing in that abyss of ineffable, inexhaustible unbeing which is the godhead.19

Eagleton contends that Burke’s concept of the sublime is rooted outside of the “daylight world of English empiricism or neoclassicism,” for it “baffles representation and ruins all stable cognition.”20 The form of this piece of artistic expression—a visual and an aural work of art—creates yet another layer of the sublime.

Roxy Music’s early recordings were within the art-pop, art-rock, and glam-rock styles, and so with an album name and cover image that is overtly Arthurian one might assume that the music itself would sound and feel grandiose and the lyrics might name-check medieval characters. Avalon’s cover image serves as an entrance into the music that is contained therein, but, with Phil Manzanera’s opening guitar riff of “More Than This,” a postmodern aesthetic chasm is created, for the music sounds nothing like the neomedievalist music of the twentieth century that was created before and after Avalon. The wizard of the keyboards Rick Wakeman is not here. His The Myths and Legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table (1975) remains a hallmark of 1970s progressive music bombast and excessive production of sound (and also physical scale when it was performed, on ice, at Wembley Arena). Wakeman’s studio album is a condensed re-telling of the life of King Arthur, with soaring lead vocals by Gary Pickford- Hopkins and Ashley Holt, members of the London Symphony Orchestra, the English Chamber Choir and the Nottingham Festival Vocal Group, and of course Wakeman’s piano and banks of synthesizers and keyboards. The music is cinematic and dramatic in style, and the choirs and the two lead vocalists (and Terry Taplin’s narration) invoke a seriousness to the concept album. Wakeman is providing us with a history of Arthur; we are to be enraptured by it, and the complex music and Wakeman’s dazzling skills are designed to keep us mesmerized and captivated. Wakeman was not the only one who explored the heroes and villains of the Middle Ages, for rock and heavy metal bands investigated these subjects as well, though with more aggressive, intense, and at times politically charged sentiments. Led Zeppelin’s song “Ramble On,” from their album Led Zeppelin II (1969), was inspired by J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, and Caitlin Vaughn Carlos observes how the band’s “sonic creation of a Middle-earth battle captures a nostalgic tone of longing. Plant’s vocal cries articulate strain and desperation, lying clearly above his comfortable tessitura.”21 The German band Grave Digger is but one of many heavy metal groups whose subject matter in songs and on full-length albums is a re-telling of the Middle Ages that can serve as creative explorations of the past and as political/social/cultural critiques of the present moment. Their album Tunes of War (1996) is a retelling of the early history of Scotland and their battle for independence; as it is heavy metal from the 1990s, the music is filled with fast, intense guitar riffs and shredding, rapid and syncopated drumming, dramatic singing, and a synthesized bagpipe.22

On the other end of the medievalism music spectrum in the twentieth century are those musicians who have mined the folk tradition of “ancient” ballads, songs, and stories, reinterpreting them through electronic instruments, such as Fairport Convention and Loreena McKennitt. McKennitt’s music can best be described as world music, and her songs incorporate British folk, Middle Eastern, new age, and neo-pagan aesthetics. McKennitt is especially interested in exploring the stories and cultures of indigenous groups, at times fusing instruments and styles from disparate cultures into one song as in “The Mummers’ Dance,” which features an oud and tabla; through her ethereal vocals, McKennitt tells of mumming celebrations that unite participants with their natural world.23 Hers is a world of fairies and sprites, of forest ghosts, and also of Arthurian subjects, most notably her interpretation of Alfred Lord Tennyson’s The Lady of Shallot on her album The Visit (1991). McKennitt’s “The Lady of Shallot” (which includes, interestingly, a balalaika) demonstrates her clear soprano vocals as she sings Tennyson’s lyrics and is accompanied by fiddle that is both plaintive and sweeping. McKennitt’s tempo throughout the song is andante, with little variation on her phrasing or the intonation of the instruments, all of which results in creating a dream-like listening experience that lulls (or bores) the audience.24

In contrast to these musicians and their styles, Roxy Music’s Avalon is a song cycle that lacks any of the medievalismist or neomedievalist tropes, styles, or trappings that the above-mentioned artists embraced. On the surface, simply by observing the album cover, Avalon could be interpreted prematurely as an album about King Arthur, or members of Roxy Music as the Knights of the Round Table and their adventures; given the band’s connections with artists who made concept albums in the 1960s and 1970s, it would be plausible. Indeed, Ferry himself characterized the album as “ten poems or short stories that could, with a bit more work, be fashioned into a novel.”25 If we consider Ferry’s own formal background in art, and reed player Andy Mackay’s in music and literature, a true concept album would not be unheard of. But the album that we have, and specifically the music, is more of an homage to the slow end of something that was once burning with desire. One way to consider the progression of the band and its music through to and including its final studio album is to think of it in terms of the band’s artistic spiraling trace. In a spiral, we of course have the intermingling of two spatial forms: the straight line, and the circle. The former is one which the Romans used as a means to visualize and conceptualize time and history as a series of events, each one more distant than the one that came before it. While the latter, the circle, was favored by the Greeks, as the perfect form, which is a marker of repetition and also of recollection.

The union of linear and circular time in the form of a spiral is one that scholars have noted when examining the narrative of a number of Arthurian texts, especially Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, where “the winding flow of the story with its consecutive episodes alternating between culture and nature, as the curve of continuous time goes around in a series of descending and ascending movements.”26 In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, we have linear progression, with the movement of one full year over the course of the poem, and yet we also have the interwoven repetition of the seasons, and the purposeful reiterative and juxtaposing scenes, characters, and themes. The poem is, rightly, the endless knot, one which can unravel at any moment as the spiral descends. This sense of difference and repetition in Sir Gawain is one that is also seen in the career of Roxy Music, with its predominant themes already noted. What sets Roxy Music apart from these artists is that the band knew that their final studio album was going to be the final album. The album was going to be where the spiral ended, and where the band would revisit its dominant themes, with the possibility of a return. Like Roxy Music’s previous albums, especially those in its first phase, Avalon was and remains a bold artistic statement. It took some guts to call your final album Avalon and also to have as its album cover an image right out of the Middle Ages.

As we move from the image of Avalon on the album’s cover to some select songs, what we notice is how the band continues to address the Arthurian Middle Ages through sublime ecological themes. Geoffrey of Monmouth in his Historia Regum Britanniae describes Avalon as the place where Arthur’s sword was forged and also where Arthur was carried after his final battle so that his wounds might heal.27 In Geoffrey’s Vita Merlini Avalon is the Insula Pomorum, the “island of apples,” which lies in the western waters and is the home of Morgan, who takes care of Arthur’s wounds after he is brought there in a boat.28 Sir Thomas Malory’s Morte Darthur and Laȝamon’s Brut both attest to the physical space as a location where Arthur will not only heal (and thus a place of stasis and rest) but also as a zone that is temporary, for he is destined to return to Britain.29 Tennyson, through Arthur’s voice, presents perhaps the most sublime depiction of Arthur’s destination:

“To the island-valley of Avilion;

Where falls not hail, or rain, or any snow,

Nor ever wind blows loudly; but it lies

Deep-meadow’d, happy, fair with orchard lawns

And bowery hollows crown’d with summer sea,

Where I will heal me of my grievous wound.”30

If Avalon is the idyllic, natural place where Arthur will rest, recover, and find solace, then this album is where Roxy Music does likewise. The arrangements on the record are more sparse, textured, formal, ethereal than on the band’s previous studio albums.

The opening track of Avalon, “More Than This,” is a song of contradictions. On the one hand, it is in F# major and the tempo is allegro. It is a song that one could dance to (either alone or with someone). “More Than This” has become a favorite karaoke song due to Bill Murray’s performance of it in Lost in Translation (2003), where his character, Bob Harris, sings it, awkwardly, while Scarlet Johansson’s character Charlotte looks on. “More Than This” is awash in percolating synths and a warm, catchy chorus. The song is also a showcase for Phil Manzanera’s guitar work, which is no longer frenetic and angular; instead, it is more refined, economical, sparse, and precise. The outro of “More Than This” is an energetic, buoyant, and happy Manzanera solo. However, the lyrics of the song bely the blissful music, for they perfectly capture the sense of ennui that engulfs the work. It is the environment that communicates to the listener that the end is approaching, for Arthur, the band, the protagonist in the song, and even those who have followed Roxy’s career:

I could feel at the time

There was no way of knowing

Fallen leaves in the night

Who can say where they’re blowing

As free as the wind

And hopefully learning

Why the sea on the tide

Has no way of turning

More than this—there is nothing

More than this—tell me one thing

More than this—there is nothing

Jonathan Rigby notes how like the tide, which Ferry describes has “no way of turning,” the “music flows on undeviatingly while Ferry drifts forlornly above it, evoking a dreamlike state in which lovers are no more secure than autumn leaves.”31

The album’s title track, “Avalon,” and the song that follows it, the instrumental “India,” represent sublime geographies and ecologies of global medievalism, which, as Candace Barrington has observed, “uses the European medieval past as a prism for interpreting, shaping, and binding cultures outside the Western European nation-states.”32 With its reggae rhythms and Caribbean feel, lyrics that reference the bossa nova and the samba, and atmospheric backing vocals of Haitian vocalist Yanick Étienne, “Avalon” jettisons the overt Anglo-centric style of Roxy’s earlier songs, and Ferry’s romantic, elegant, yearning croon (which is present throughout the album) situates the listener in a purely contemplative mood. Likewise, “India” is an abrupt departure, both in name and feel, to the Roxy catalogue, for it overtly draws attention to a non-Western setting and creates a sound that is lush and exotic through its instrumentation, percussion, and rhythm. This is not the India of the East, however, and the scales are not pentatonic. Indeed, these are the West Indies, and they serve as both a physical space of creation for the band and also as an extended geographic metaphor for global Arthurian medievalism. Avalon was recorded at Compass Point Studios in Nassau. The studios were founded in 1977 by Chris Blackwell, founder of Island Records, who was responsible for bringing the music of Caribbean artists such as Bob Marley and the Wailers, Toots and the Maytals (who introduced the word “reggae” to listeners in their song “Do the Reggay”), and Grace Jones to the wider world. The setting of the studio at Compass Point, with its tropical flora and fauna, its position on the coast, and the warm wind and waves that enveloped the musicians, connects this island of musical creativity with the medieval islands of Arthur’s Britain and his own Avalon. Moreover, Roxy Music’s venture to Compass Point and their embrace of its Caribbean musical culture echoes the imperial desires of Arthur that are realized in nineteenth-century Britain through global territorial expansion. In songs such as “Avalon” and “India,” Roxy Music is neither advocating for colonialism, nor is it critiquing several centuries of the detrimental effects of British colonial rule. Instead, these songs and the album allowed the band—and continuously allow the listener—to enter into a landscape that represents an Earthly paradise, one that is distant, though familiar, and one that has the potential to bring succor. The opening lines of “Avalon” position the singer, the listener, and even Arthur within that space of physical, spiritual, creative enervation: “Now the party’s over / I’m so tired.” However, on the horizon, there is an/the Avalon and “India,” where there is hope for renewal. Within these landscapes, Roxy Music’s recursive Arthurian medievalism is one that demonstrates the global reach, influence, and impact of Arthurian sublime space.

Avalon’s final track, “Tara,” like the opening song, is one that embraces the environs of Avalon. The song is one of two brief instrumentals on the album, and it is marked by a beautiful soprano saxophone solo, which was improvised by Andy Mackay and caught on tape. Over Mackay’s beautiful lines are layered Ferry’s keyboard soundscapes, Alan Spenner’s hushed base notes, and the sound of the waves. Are we nearing Avalon? Are we hearing a field recording of the waves outside of Compass Point Studios? Both of those are possible, and perhaps that is what Roxy intended us to imagine, to be metaphysically transported to either or both. In truth, we are in another “Avalon.” Ferry taped the sound of the waves outside of Crumlin Lodge, a house and setting that reminded him of Scarlett O’Hara’s ancestral home, Tara, in Gone with the Wind.33 Tara, too, has its own important place in the history of Ireland, for the Hill of Tara, the Tara Brooch (ca. 700 CE), and the Battle of Tara (980 CE), are some of the physical remnants of a medieval Celtic past that remain and have helped to shape the importance of its mythologies and histories.34 The winds and the waves that brought Arthur to Avalon can, at some unknown point, return him to Britain. Like Bran in the early Irish Story Immram Bran, with “Tara,” and the album as it nears its conclusion with the solitary, solemn sound of waves, we are taken to an Otherworld, where the “sea is the watery plain and atmosphere that seem to encompass a parallel reality,” one that is perhaps a “paradisiacal spiritual dimension.”35

Roxy music’s Avalon exemplifies a confidence in natural forms; indeed, as a work of neomedievalism, it is a text whose embrace of technology is used as a means of communication to the listener and the viewer of the power and function of the sublime in the re-presentation of the landscape of the Middle Ages. C. Stephen Jaeger’s words on “charismatic art” seem appropriately apt when looking at and listening to the album, for the purpose of such art is “to create a world greater and grander than the one in which the reader or viewer lives, a world of sublime emotions, heroic motives and deeds, godlike bodies and actions, and superhuman abilities, a world of wonders, miracles, and magic— in order to dazzle and astonish the humbled viewer.”37 With Roxy Music’s Avalon, we are reminded that while the Middle Ages are forever in the past, their intersectional environmental, literary, and sublime traces continue to be felt. Much like Arthur’s sojourn, after more than thirty years in its own Avalon, Roxy Music’s studio career continues to remain shrouded in mystery, awaiting a possible return in the future.

- The band’s debut album Roxy Music was issued in June 1972; the album quickly was followed in August 1972 by one of the most daring, innovative, and nostalgic stand-alone singles to date: “Virginia Plain.” As the band’s music and style progressed along its ten-year path of eight studio albums, certain tropes and motifs became more prevalent than others. This first phase of Roxy was truly an extension of 1950s rock- and-roll: the exuberance of falling in love, the pull and power of romantic and idealized love, and the nostalgia of past dalliances. There is, however, a prevailing sense of purposeful kitsch and irony, not only in the songs’ lyrical content but also in their textures: the band’s roots were firmly in American rock-and- roll, yet the sounds and images were futuristic. There was something familiar about the content, but the form and execution were unusual: a fantasy world set in the present, yet without special effects. The listener, through Roxy’s cypher, Bryan Ferry, is brought into the general milieu of the music. As one listens to Roxy’s first five albums, the repetition of these themes of passionate love, desire, and intense sexuality are overt, and the style of these songs often alternate between the hyper-kinetic rockers such as “Love Is the Drug” and “Both Ends Burning,” and the slinky, lounge-lizard numbers of “A Really Good Time,” “Mother of Pearl,” and “All I Want Is You.” After Siren (1975), the band embarked upon a four-year studio album hiatus and returned in 1979 to a noticeably different music scene. The final three Roxy Music studio albums (Manifesto, Flesh + Blood, and Avalon) are more densely-textured affairs and look ahead to the New Romantics of the early 1980s. The frenetic rock and roll attitude is gone, replaced with introspective, stylized, contemplative, and sophisticated music.

- Dan Nastali in his essay “Arthurian Pop: The Tradition of Twentieth-Century Popular Music” comments thus: “The concept of Avalon, without reference to Arthur, continued to inspire songwriters, notably Bryan Ferry, whose ‘Avalon’ (1982), on the album of the same title by Roxy Music, alluded to an unknown destination while background vocalists repeated the word ‘Avalon’ again and again in refrain,” in King Arthur in Popular Culture, ed. Elizabeth S. Sklar and Donald L. Hoffman (Jefferson: McFarland, 2002), 138-67, 148. More recently, Gail Ashton has used a number of the album’s song titles as thematic section headers for her edited volume Medieval Afterlives in Contemporary Culture (London: Bloomsbury, 2015).

- Amy S. Kaufman, “Medieval Unmoored,” in Studies in Medievalism XIX: Defining Neomedievalism(s), ed. Karl Fugelso (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2010), 1-11, 4.

- David Buckley, The Thrill of It All: The Story of Bryan Ferry and Roxy Music (Chicago: A Capella Books, 2004), 23.

- Buckley, The Thrill of It All, 23.

- Buckley, The Thrill of It All, 25.

- ITwo of Roxy Music’s album covers contain literary allusions and thus may anticipate the Arthurian matter of Avalon: 1975’s Siren and 1980’s Flesh + Blood. The former depicts Jerry Hall as a siren, one who is crawling up and onto a rocky shore and toward the viewer; the entire cover image is awash in blue tones, with only Hall’s red lipstick and golden hair and headpiece breaking the visual frame. The latter features three Amazonian-style spear throwers, of whom two (Aimee Stephenson and Shelley Mannare) are on the front of the album and a third (Roslyn Bolton) on the back; all are dressed identically in white, sleeveless gowns, and their bodies are leaning on and supporting one another in their martial action.

- From author’s personal collection.

- Jonathan Rigby, Roxy Music: Both Ends Burning (London: Reynolds and Hearn, 2005), 245.

- Rigby, Roxy Music, 245.

- See the following three-in-one volume: Aristotle, Poetics, trans. Stephen Halliwell. Longinus, On the Sublime, trans. W. Hamilton Fyfe, rev. trans. Donald A. Russell. Demetrius, On Style, trans. Doreen C. Inness and W. Rhys Roberts, Loeb Classical Library 199 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), Longinus, On the Sublime, 9.189.

- Alfred Kentigern Siewers, “Introduction—Song, Tree, and Spring: Environmental Meaning and Environmental Humanities,” in Re-Imagining Nature: Environmental Humanities and Ecosemiotics, ed. Alfred Kentigern Siewers (Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 2014), 1-41, 25-6.

- Longinus, On the Sublime, 9.191.

- Marilyn Gaull, English Romanticism: The Human Context (New York and London: W. W. Norton, 1988), 231-2.

- Gaull, English Romanticism, 232.

- Terry Eagleton, “The Irish Sublime,” in “The Endless Knot: Religion and Literature in Ireland,” special issue, Religion and Literature 28, no. 2/3 (1996): 25-32.

- Eagleton, “The Irish Sublime,” 25.

- Siewers, “Introduction,” 25.

- Eagleton, “The Irish Sublime,” 25.

- Eagleton, “The Irish Sublime,” 29.

- Caitlin Vaughn Carlos, “‘Ramble On’: Medievalism as a Nostalgic Practice in Led Zeppelin’s Use of J. R. R. Tolkien,” in The Oxford Handbook of Music and Medievalism, ed. Stephen C. Meyer and Kirsten Yri (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 530-46, 535. The other two Led Zeppelin songs that Carlos analyzes are “The Battle of Evermore” and “Misty Mountain Hop.”

- For an engaging collection of essays on heavy metal and medievalism, see Ruth Barratt Peacock and Ross Hagan, ed., Medievalism and Metal Music Studies: Throwing Down the Gauntlet, Emerald Studies in Metal Music and Culture (Bingley: Emerald Publishing, 2019).

- “The Mummers’ Dance” can be found on McKennitt’s album The Book of Secrets (1997).

- For a survey of Tennyson’s poem in art and song, see Margarita Carretero González, “Floating Down Beyond Camelot: The Lady of Shallot and the Audio-Visual Imagination,” in Into Another’s Skin: Selected Essays in Honour of María Luisa Dañobeitia, ed. Mauricio D. Aguilera Linde, María José de la Torre Moreno, Laura Torres Zúñiga (Granada: Granada Editorial Universidad de Granada, 2012), 244-54. Many thanks to Melissa Ridley Elmes for alerting me of this reference.

- Rigby, Roxy Music, 245.

- Piotr Sadowski, The Knight on His Quest: Symbolic Patterns of Transition in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Presses, 1996), 71.

- Geoffrey of Monmouth, The History of the Kings of Britain, trans. Lewis Thorpe (Baltimore: Penguin, 1966), 261.

- Geoffrey of Monmouth, Avalon from the Vita Merlini, trans. Emily Rebekah Huber. The Camelot Project: A Robbins Library Digital Project at The University of Rochester, http://d.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/text/geoffrey-of-monmouth-avalon-vita, accessed June 1, 2015.

- Sir Thomas Malory, Le Morte Darthur, ed. P. J. C. Field, Arthurian Studies 80 (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2013), 1: 927.4-7; Laȝamon, Brut, or Historia Brutonum, ed. and trans. W. R. J. Barron and S. C. Weinberg (New York: Longman, 1995), 732.14277-82.

- Alfred Lord Tennyson, “The Passing of Arthur,” in Idylls of the King, ed. J. M. Gray (London: Penguin, 1983), 288-300, lines 299.427-32.

- Rigby, Roxy Music, 248.

- Candace Barrington, “Global Medievalism and Translation,” in The Cambridge Companion to Medievalism, ed. Louise D’Arcens (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 180-95, 183.

- Rigby, Roxy Music, 258.

- For an important volume on Tara, see Edel Bhreathnach, ed., The Kingship and Landscape of Tara (Dublin: Four Courts Press for the Discovery Programme, 2005).

- Alfred K. Siewers, Strange Beauty: Ecocritical Approaches to Early Medieval Landscape, The New Middle Ages (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 3.

- C. Stephen Jaeger, Enchantment: On Charisma and the Sublime in the Arts of the West, Haney Foundation Series (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), 41.[/efn_note Therefore, such a sublime work of art creates an astonishment that “overwhelms the narrow rationalism that sees in the work of art only illusion, not higher or heightened reality.”36Jaeger, Enchantment, 182.